Java generics and inheritance (part 1)

Learn about java generics and inheritance with Dario!

Types, Sets, variables and casting

When you use a compile-time typed language, like Java, you expect that types in each variable will help you by restricting the possibilities for a value. Instead of being able to do everything, you want to do things that are valid in your domain.

Discussions aside about strong vs weak typing, when you code with types you think of types as sets. A variable can be one of the elements of the implicit set for its type. Thus Integer a means that variable 'a' will be one of the elements in the Integer set, and only that.

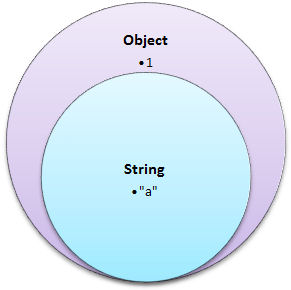

If you have a String variable 'a' and want to assign its value to a variable 'b' of type Object:

String a = "A";

Object b = a;

The compiler does an implicit up-casting and you expect that to be a valid operation. The set of Object instances is a super-set of String instances. That is basically because Object is a superclass of String and inheritance implies set inclusion.

But once you upcast, you lose specificity. Your set of possibilities gets bigger and you can't ensure that 'b' will always be a String. The value of variable 'b' could be the String a, or could be something completely different like the number 1, that belongs to the Integer set.

So far, I haven't told you anything new.

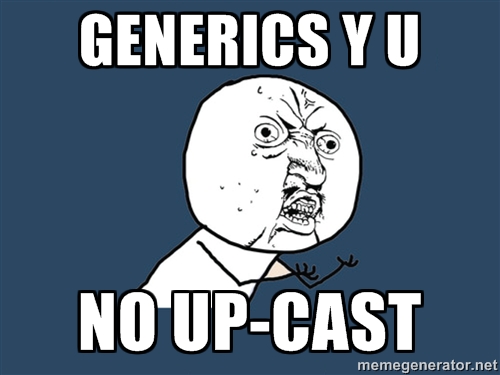

What's wrong with generics?!

If you use Java generics, it's fairly probable that you have tried this example wondering what is wrong with the compiler:

List<String> stringList = new ArrayList<>();

List<Object>objectList = stringList; //error: cannot convert from List<String> to List<Object>

If List<Object> is the set of all lists that have objects inside, then List

To complicate things worse, the compiler will accept that same reasoning for arrays:

String[] stringArray = new String[0];

Object[] objectArray = stringArray;

Why can arrays be assigned and lists cant't? Have you ever dedicated some thoughts to it? They are both container types, they have both just one element type. What makes those types conceptually different?

The reason

Reading the authors of generics you can find a very good reason for it. Remember, at that time, they were trying to generify collections (having only java 1.4 on their hands).

If you allow a list of strings to be upcasted to a list of objects and operated as a list of objects, you can do something like:

List<String> stringList = new ArrayList<String>();

List<Object> objectList = stringList; // Let's pretend this is possible

objectList.add(1); // Hey, 1 is not a String!

String element = stringList.get(0); // Wonder what will happen...

Since it's an object list, why can't you just put a number inside. It's an object right? And what happens when the reference to that same list instance but with a List<String> type tries to get the added element?

String element = stringList.get(0);

Yeah! KaBoom. ClassCastException!

Wait, what? Why do I have a cast exception if I'm not even casting?

To understand what's is going on, we need to see the implicit code there. When you use generics you have what they called "erasure": the compiler modifies your code and some of the generic information is lost. This is the actual runtime code:

String element = (String) stringList.get(0);

You are not only casting, you are down-casting (which it's not runtime-safe). The return type of get() method, in runtime, is Object, not String. That's why, in runtime, you need to downcast to String.

The compiler does it for you, but at the cost of assuming that the list only contains Strings. That assumption can be made at compile time if you avoid addition of other non String objects. How do they do that?

At compile time, let's not allow the list to be used for anything else than Strings. So list of objects is out of the question.

There are, of course, other solutions to this problem (see Covariance and Contravariance ) but we will stick to Java solution in this article.

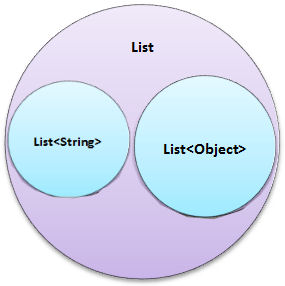

If you know what you are doing, there's one way to workaround this generics restriction. To see it graphically at compile time, we have three types List<String>, List<Object> and List which is the "raw" type, represented as sets:

The only way to escape this rule, at compile time, is to move to the super-set, and then go down to the other sub-set.

List<String> stringList = new ArrayList<String>();

List<Object> objectList = (List)stringList; // no error

Fool the compiler by up-casting to List so it doesn't know which kind of elements is in the list, and then down-cast to List<Object> which is accepted. Why is that allowed and (List<Object>)stringList isn't, it's out of my grasp.

Just to warn you: if you manage to do this, you may have ClassClassExceptions in runtime.

But arrays!

On the next part of this article, I'll show you why this doesn't happen with arrays, and the implications for reflection.